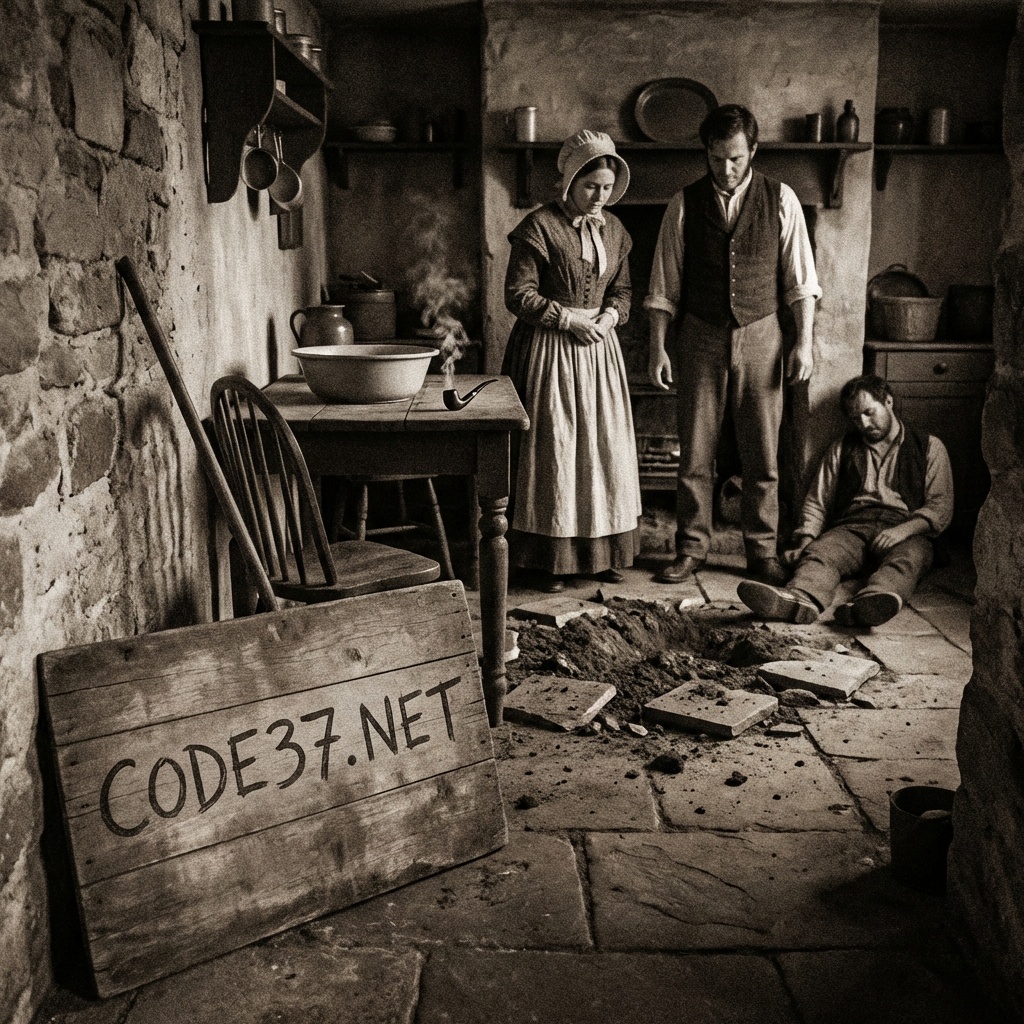

Véronique Frantz, born around 1825, is a fascinating, albeit dark, figure in French criminal history. Her story takes place in Alsace and unfolds in a combination of love, jealousy, and deadly desire. Driven by her insatiable desire to win the man of her dreams, she stopped at nothing, not even resorting to poison. In 1848, Frantz was hired as a maid in the house of winegrower George Guntz in Nothalten. She was hard-working and conscientious, which earned her the respect and affection of the family. Nevertheless, she had a strong will and often a dominant character, which did not always meet with approval. The family, including Guntz’s wife Marie-Elisabeth Ruhlmann, trusted her blindly. But as is often the case with hidden ambitions, desires germinating in the darkness blossomed. This was also true of Véronique. At the end of November 1852, after Guntz’s wife Marie-Elisabeth had been ill, Guntz said in a moment of candor that he would consider Véronique as a possible marriage candidate if his wife were to die. This remark awakened a consuming desire in Véronique. She began using the arsenic stored in bottles in the attic to poison the family. Her first attempt resulted in many family members becoming extremely ill, but they survived. However, this would not go well for long. Véronique knew that time was running out and that she had to act quickly. Under pressure, Guntz’s mother-in-law, 75-year-old Marie-Anne Kobleth, threatened to leave the house if Frantz was not fired, as she did not trust her. But Guntz refused. In her desperation, Véronique continued with the poison cocktail and eventually poisoned Kobleth’s drinks. On December 1, 1852, Kobleth died of arsenic poisoning, further increasing Véronique’s influence in the house. With Kobleth’s death, Véronique felt that she finally had control over the family. But she wanted more. The death of Guntz’s wife Marie-Elisabeth on July 6, 1853, was a boost for Véronique. She believed that she could now become Guntz’s beloved. But to her horror, Guntz announced that he wanted to marry another woman. Angry and disappointed, Véronique radiated this and intensified her poisoning attempts. Guntz finally died on January 27, 1854, and Véronique thus concluded her deadly series. A young boy and Guntz’s father survived, but continued to struggle with the symptoms of poisoning. After Guntz’s death, the villagers began to suspect something was amiss. An autopsy confirmed their suspicions when arsenic was found in Guntz’s organs. The remains of Kobleth and Ruhlmann, who were also believed to be victims of Véronique, were quickly examined. Although Véronique initially denied any guilt and protested her innocence, she was eventually overwhelmed by the overwhelming evidence. Véronique ultimately confessed to the murders. During her trial, she was subjected to intense questioning by the prosecutor, M. Dubois. Despite her refusal to answer questions about why she had poisoned Guntz, she was found guilty. On June 17, 1854, the court handed down its verdict: Véronique Frantz was sentenced to death. She remained cold and composed throughout the trial, sending shivers down the spines of those present. During her time in prison, she turned to religion, prayed a lot, and sought comfort in spirituality. On the day of her execution, she was accompanied by gendarmes and an abbot. On the guillotine, Véronique Frantz said a final prayer before she was executed. Her last meal consisted of a cup of café au lait and a roll. A simple farewell for a complex soul. The story of Véronique Frantz is a dark chapter in French criminal history. Her actions were the result of a deep-rooted desire for love and power that ultimately led to her downfall. Upon her death, the town of Barr remembered the horrors that had taken place within its walls in previous years, and her story remains a cautionary tale to this day of how far people are willing to go to fulfill their desires. Even if it means walking over dead bodies.